- English

- Covenanted Happiness: Love and Commitment in Marriage (Third Edition, 2009)

- The Lawless People of God? (2nd edition, 2009)

- Conscience and Freedom (Sinag-Tala, 1992. 2nd edition)

- Man and Values - a Personalist Anthropology (Scepter, 2013)

- A Postscript to the "Remedium Concupiscentiae"

- Revised Knox Bible ('you' version)

- The Object of Matrimonial Consent - A Personalist Analysis (Forum 1998)

- Authority and Freedom in the Church (Ignatius Press, 1988)

- 01. The Lawless People of God?

- 02. Lawlessness and Society

- 03. Individualism and the Church

- 04. Freedom

- 05. Conscience

- 06. Dissent

- 07. Dissent and the Rights of the Faithful

- 08. Law as a Gift

- 09. Law and the Holy Spirit

- 10. The Church: Juridical or Charismatic?

- 11. Authority, Power, Service

- 12. Roles in the Church; Roles in the World

- 13. Authority and Evangelization

- 14. Authority and Truth

- 15. Truth and Definition

- 16. Truth and Communion

- 17. Communion, Unity, Diversity

- 18. Appendix I. Legal Positivism

- 19. Appendix II. Natural Law

- 20. Appendix III Abuse of Authority

- Married Personalism - a Debate (publication pending)

- The Cardinal Virtues: Feminine Perspectives

12. Roles in the Church; Roles in the World

Wed, 07/28/2010 - 09:32 — webmaster

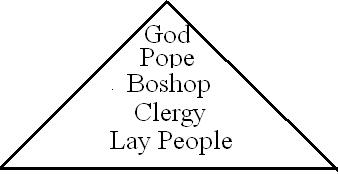

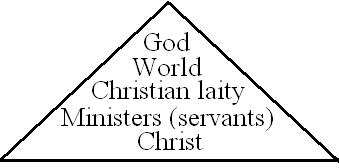

One day, in a seminar with theology students I sketched out the two pyramids of the last chapter, side by side:

Where indeed is the world? It is a telling comment that suggests further defects - which in fact represent a major gap - in the power-struggle mentality.

The theory that clergy and laity are competing for "power" takes energies - the salt and light and leaven of Christianity - that are meant to be directed towards the world, for its transformation, and turns them inwards, to be consumed in sterile and at times acrimonious debates about church organization and structures and functions.

It is questionable if such an in-turned ecclesiology can renew the Church. It is certain that it cannot renew the world. What sort of church-view do we have if it is not big enough to embrace the world? The Church is not a closed system. It exists not for its own sake, but for the sake of the Gospel, for the sake of the world: to bring the message and work of Christ to the whole world. Of its nature the Church must be open to the world - so as to save the world. A church-view that is not at the same time a world view is radically defective.

To this the reply might be made that the power-sharing thrust is a necessary process or stage in renewal; that the Church, once renewed in this way - with the laity given their proper status and able to play their proper role - will then be an effective instrument of evangelization. In other words, a renewed - and evangelizing - Church depends on the laity having their proper role opened to them.

This is interesting; it suggests that we should refocus our attention, transferring it from the question of power to that of roles. If we do, I think we can show that a misconception of power or authority is only one side of the coin of the power-pyramid mentality; for there is another side which is a radical misunderstanding of ecclesial and Christian roles: the proper role of the clergy and, especially, the proper role of the laity.

The role of the clergy has been sufficiently considered in the last chapter. It is a ministerial role of service primarily to the People of God. The people need the fulltime service of the ordained priest living, acting and ministering among them in a priestly way that is clearly identifiable as such. A priest shows his solidarity with the people by serving them in a priestly way, not by imitating their secular life-style. The imitation by a priest of lay ways is not welcomed by the vast majority of the laity, and in far too many cases it leads to a loss of identity and sense of mission on the part of the priest himself. But we will not expand further on that, as the purpose of this chapter is rather to study the proper role of the laity.

The proper role of the laity

Can anyone be seriously satisfied with the idea that the desired "advancement of the laity" lies along the lines of the lay ministries we mentioned in the last chapter? Lay ministries obviously merit our respect as a genuine service to the ecclesial community. Yet these ministries, and all the current projections more or less connected with them, have very little to do with the true role of the laity as presented by Vatican II.

Few people seem to advert to the evident danger of the gradual "clericalization" of those lay people who follow a way of active engagement in roles formerly (and still, of course, mainly) associated with the clergy[1]. Fewer still advert to another point that should also be evident: the enormous majority of lay people simply cannot go that way.

A few moments reflection shows this. What percentage of the lay members of a parish can be actively involved in liturgical roles or in pastoral or administrative positions? Two per cent? Five per cent? What then of the other 95 per cent? Have they no proper church role? And, of the 5 per cent who are active, what percentage of their time - i.e. of their normal week - is spent in such church activities? Ten per cent? What then of the remaining 90 per cent of their week spent in their job, family, etc.? Is all of that marginal or unimportant? Is it of no real ecclesial significance? Is it a second- rate activity before God? Has it no apostolic potential or value? Does it not properly fit into their role as Christians?

How can advancement of the laity lie along a path that can be followed, in the best of cases, by only a tiny fraction of lay people, but which remains an ecclesial dead end for all the others? If advancement of the laity means this, then it is a way that is blocked to the vast majority (blocked, be it noted, not by ecclesiastical obstructionists, but by the very conditioning factors of the laity's own life).

If the role of the laity is not in the line of lay ministries, where does it lie? Vatican II is totally explicit about the distinctive role of the laity and the field in which it is to be exercised. The proper field of the laity is the world. It is in the world that they have to sanctify themselves, each one being an incarnation of the spirit of Jesus Christ in his or her secular activities. And it is in the world, on the basis of that union with Christ, that they are also to be evangelizers, striving to penetrate the whole human order with the saving and vivifying power of Christ.

"By reason of their special vocation it belongs to the laity to seek the kingdom of God by engaging in temporal affairs and directing them according to God's will" (LG 31)[2]. They have "to animate the world with the spirit of Christianity" (GS 43); "to sanctify the world from within" (LG 10, 31); "to permeate and perfect the temporal order with the spirit of the Gospel" (AA 2; cf c. 225).

"The laity are given this special vocation: to make the Church present and faithful in those places and circumstances where it is only through them that she can become the salt of the earth" (LG 33). "The characteristic of the lay state being a life led in the midst of the world and of secular affairs, laymen are called by God to make of their apostolate, through the vigor of their Christian spirit, a leaven in the world" (AA 2).

The priestly, prophetic and kingly office of the laity

The proper role of the laity then is not to share in clerical power. It is to share in the power and mission of Christ, so as to impregnate their own secular lives, and the world around them, with his spirit.

Following the thought of the Council we can spell out the distinctive way in which the laity participate in the mission of Christ, specifically in his three-fold office (cf. LG 31ff; AA 10).

Their share of the priestly office of Christ implies, of course, a life centered on the Eucharist. But their eucharist participation is not only expressed by their being actively present in Mass, nor is it mainly expressed by particular liturgical roles performed in church. It is by "worshipping everywhere and in everything by their holy actions (that) the laity consecrate the world itself to God" (LG 34). And so "all their works, prayers and apostolic undertakings, family and married life, daily work, relaxation of mind and body, if they are accomplished in the Spirit - indeed even the hardships of life if patiently borne - all these become spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ" (ibid).

So their share in the priestly office of Christ is expressed above all and essentially in their struggle to sanctify their everyday work and secular activity.

What about the share of the laity in the prophetic or teaching office of Christ? The Council insists that Christ "fulfills this prophetic office, not only through the hierarchy who teach in his name and by his power, but also through the laity. He accordingly both establishes them as witnesses and provides them with the appreciation of the faith and the grace of the word so that the power of the Gospel may shine out in daily family and social life" (LG 35; cf no.12).

For a lay person to announce the word of God in church is no doubt an exercise of this prophetic function. That this is now done where it was not done before may well be considered an advance. But if our perspective advances along that road alone, we are, I repeat, looking down a dead end.

Where the specific vocation of the lay person calls him to announce the word of God is not in the church but in the world: in his factory, in his office, in his club, in his family. He has to do this not only by his example but also by directly communicating doctrine - i.e. his knowledge of the faith - ensuring that in his prophetic mission it is truly the word of God that he communicates. It is not in "sermonizing" that he will do this (the role of preacher fits the layman poorly) but in the normal exchange of views among colleagues and friends, where the impact of the Christian truth inspiring him will hit home.

His prophetic role also means that he is not afraid to bear witness to the word when it is unpopular, nor is he discouraged or tempted to convey a watered-down version of the word when it appears to be rejected or when he faces persecution (cf Mt 13:21). The Council insists that the laity must not hide their hope or faith, but rather "express it through the structure of their secular lives in continual conversion and in wrestling 'against the world rulers of this darkness, against the spiritual forces of iniquity' (Eph 6:12)" (LG 35).

And the kingly role of the laity? It is on the basis of the grace and truth of Christ that the laity must set about fulfilling, in the world, their Christian ruling mission. It is here that the greatness of the challenge facing them becomes more apparent; it is here too that partial understandings or fundamental misunderstandings can most easily arise.

Christ the Lord and Savior of all creation wants to serve, save, rule the world, raising it to God. He does so through his Church: through his ministers, but more immediately still through his lay followers.

The first aspect of the lay Christian's kingly role relates to his work in its personal dimension, and is simply enough expressed. He is meant to be king in relation to his personal work, as Christ was King of the everyday work he performed during those thirty hidden years.

This means that the Christian in his kingly role is meant to dominate work, not to be dominated by it. He should realize that his work, to which he freely dedicates himself, is not just a means to money or self-affirmation. It serves a divine plan. And he should rule and direct his work to the fulfillment of this plan[3].

Ruling the world

But the kingly role of the laity has a more ambitious scope still. Man is placed to rule and shape all creation. Christ empowers his lay followers, most especially, to exercise this rule on his behalf The Council speaks in noble and solemn terms of the task facing the Christian laity: the task of establishing the kingdom of Christ in the world. "The Lord desires that his kingdom be spread by the lay faithful also: the kingdom of justice, love and peace. In this kingdom creation itself will be delivered from the slavery of corruption into the freedom of glory of the sons of God (cf. Rom 8:21). Clearly, a great promise, a great commission is given to the disciples: 'all things are yours, you are Christ's, and Christ is God's' (1 Cor 3:23). ... The laity enjoy a principal role in the universal fulfillment of this task" (LG 36).

The laity's role is not enhanced when they look for or are given a share in clerical authority or service. They can go in that direction. But not many can go; and it is not their proper direction. Their share in the kingly mission of Christ is not essentially there but in the world. Their "primary and immediate task is not to establish and develop the ecclesial community - this is the specific role of the pastors - but to put to use every Christian and evangelical possibility latent but already present and active in the affairs of the world"[4]. They are not meant to be mini-priests or supersacristans; they are meant to be the light and salt of Christ's presence in the secular world.

In one of the passages from Lumen gentium quoted above, the Council says that the distinctive vocation of the laity is not only to engage in temporal affairs but also to "direct them according to God's Will" (LG Si). This sends out a powerful call and challenge to the laity. It underlines that their role is to exercise the authority of Christ in the world, not merely by giving moral guidance as the hierarchy especially do, but by actively guiding and directing secular affairs - professions, business, politics, trades-unions, culture, education, mass media, entertainment, social and family life - by their forceful presence and courageous leadership. There is where, by ruling, guiding, serving, they exercise the kingly authority of Christ. "The effort to infuse a Christian spirit into the mentality, customs, laws, and structures of the community in which a person lives, is so much the duty and responsibility of the laity that it can never be properly performed by others" (AA 13).

The kingly mission of the laity involves permeating the whole social order with those Christian principles which humanize and elevate it: the dignity and primacy of the human person, social solidarity, the sanctity and inviolability of marriage and the home, the principle of responsible freedom, love for the truth, respect for justice at all levels, the spirit of service, the practice of mutual understanding and fraternal charity...

Why should lay Christians want to run the Church - when they are meant to run the world? The challenge to the laity is not to "overtake" the clergy, it is to "take over" the world.

Here is where misunderstanding might arise. It could be grave and needs to be avoided; although those who are no friends of Christianity, or of evangelization, are not likely to avoid it.

This lay Christian rule or "running" of the world will not imply or involve clerical domination or ecclesiastical penetration of secular society. It will mean the world animated by ordinary citizens who truly understand the world and love it; and so, respecting its distinctive secular nature, can lead it to its proper fulfillment and end.

"Let Christians be proud of the opportunity to carry out their earthly activity in such a way as to integrate human, domestic, professional, scientific and technical enterprises with religious values, under whose supreme direction all things are ordered to the glory of God" (GS 43).

"It pertains to the laity in a special way so to illuminate and order all temporal things with which they are so closely associated that these may be effected and grow according to Christ and may be to the glory of the Creator and Redeemer" (LG 31).

The Christian renewal of the world will mean the world enlightened with the light of Christ (LG 36). And this light will be spread above all by individual Christians acting not as "agents" of the Vatican, not on orders from the hierarchy or from some particular church institutions, but precisely as individual citizens possessing and exercising full personal freedom and full personal responsibility (cf. AA 7).

We are evidently not suggesting that the clergy have no specific mission in the world. Of course they have. The whole Church has (AA 7). The clergy fulfills a sanctifying mission through ways of prayer and worship whose effect goes beyond any human power of appreciation. The effect of the clergy's prophetic mission to the world is more evident. The hierarchy has to preach the Gospel, "welcome or unwelcome" (2 Tim 4:2), declaring to the world, time and again, the eternal principles of the law of God and the plan of Christ.

However, as we know, men frequently do not listen to the clergy. The fact is that, from the world's point of view, the clergy and the hierarchy often appear as "outsiders". They may want to go to the world, to preach the Gospel. But so often the way to the world is blocked to them; physically or morally. Men's doors - factory doors, office doors, assembly doors, neighborhood doors - are often closed to them. Men's ears too are often closed to them.

Christian lay people in the world are "insiders". They do not have to go to the world; they are already there. They are in the world, as ordinary citizens, like the rest of their fellow-men - to whom, in so many cases, they and they alone can be effective evangelizers. "It is a fact", the Council emphasizes, "that many men cannot hear the Gospel and come to acknowledge Christ except through the laymen they associate with" (AA 13).

Christian lay people have to exercise their "kingly service"[5] by leading their fellowmen to Christ. How are they going to do this? They are not going to do it by subterfuge, evidently; Christ wants clarity and openness. Nor are they going to do it at the point of a gun; Christ does not want coercion or violence. He is only interested in free followers. I think we can underline two main requirements which Christian lay people (always on the basis of their personal union with our Lord) must meet to carry out their role "to spread the divine plan of salvation to all men of every epoch all over the earth" (LG 33).

Competence and doctrine

The first element necessary if Christian lay people are going to lead and guide human affairs is competence: competence in their profession or job. Their right to hold directive positions in secular affairs is something to be won on sheer professional merit, on the quality of their study, training and research, and on the quality of their actual work. In expounding the kingly mission of the laity, the Council insists on this precise point: "by their competence in secular disciplines and by their activity, interiorly raised up by grace, let them work earnestly in order that created goods through human labor, technical skill and civil culture may serve the utility of all men according to the plan of the Creator and light of his word" (LG 36).

It should be clear that lay people with a true sense of their Christian vocation have every reason to acquire outstanding professional competence. After all, since sanctity is what they seek in and through their job, love for God is the mainspring impelling them to work. And this motive is higher than the noblest human motive and more powerful than the most self-centered ambition; therefore they work and work a lot.

The other element Christian lay people need if they are going to lead the world to Christ is doctrine. The Council again is very specific on this. Insisting once more that "laymen ought to take on themselves as their distinctive task this renewal of the temporal order", the Decree on the Apostolate of Lay People adds that their direct and specific action in this field must be "guided by the light of the Gospel and the mind of the Church, prompted by Christian love" (AA 7). And Gaudium et spes adds that it is the task of the laity "to cultivate a properly informed conscience and to impress the divine law on the affairs of the earthly city" (no. 43). When professionally competent lay people have assimilated the message of the Gospel and attuned their minds to the mind of the Church (Christ speaking to us in both), then, under the prompting of Christian love, they are qualified to lead the world.

If faith in Christ and love for him are the real mainsprings of the lay person's competence and doctrine, then he will possess unity of life; thus, living in an incarnational way (cf. AA 4), he will avoid that divorce between faith and daily life which the Council describes as "one of the gravest errors of our time" (GS 43).

As we can see, then, the role of the clergy and the role of the laity are complementary but distinct. The role of each Christian, in answer to the universal call to holiness (cf. LG, chap. V), is a role of service and evangelization, modelled on Christ the Servant and the Savior of all: the clergy serving mainly within the Church; and the laity serving essentially within the world. The priest has to be Christ to the Christian laity, in a priestly way. And the laity have, in a lay way, to be Christ to the world.

In the last chapter we criticized the "power-sharing" mentality, when it presents clergy and laity jostling each other for positions of"influence" within the Church. This, we tried to show, betrays a poor understanding of power or authority within the Church. Nevertheless, the notion of power-sharing can of course be refined and expressed in a proper sense. If authority is understood as service, then "power-sharing" becomes service-sharing: each one, by serving in his or her proper way, shares in the power of Christ to save the world.

Each in his or her proper way: this is the key to the matter. That is why the nature of ecclesial power cannot be adequately clarified without at the same time clarifying the nature of ecclesial roles. The "power" of each Christian is the power to serve in the specific role God has given each one. To want a different power is to want not to serve.

Who is going to be the boss?

Why is it that more than twenty years after the Council these notions of roles and service are still so imperfectly grasped? The answer, I think, is that the spirit of clericalism is a hardy body; it can assume new forms but it takes a long while to die.

Already before the Council there was a reaction against the centuries-old tradition of regarding the laity as the passive "praying-paying-obeying" members of the Church. Vatican II gave guidelines for a truer concept of their ecclesial role. It is questionable, however, if these guidelines have been properly understood on any broad level or if they inspire much of the post- conciliar debate about means of "promoting" the laity.

The fact is that the clerical mentality which characterized so much thinking about the laity before the Council has (despite appearances) largely continued to dominate thinking on the same subject even after Council. It has changed its tone and presentation, but it reasons from the same defective appreciations.

The caricature of the autocratic pastor of thirty years ago showed him with a sign hanging outside his parish office; "I AM THE BOSS". Whatever the truth in the caricature (and there was undoubtedly some), this is taken today to represent the pre-conciliar clerical mentality: "We are the bosses".

Since the Council there has been a growing number of clerics telling the laity, with apparent generosity, "Come. We will share our power. You can be bosses with us". And there is a number of lay people insisting, "We want a share in that power of yours. We want to be bosses with you (or even without you...; or, if necessary, against you!)"

The first comment that comes to mind is that we are not thinking like Christ if we squabble about who is going to be boss (Mt 20:28). In any case, all of this - whether pre- or post-conciliar - betrays the same substantial misconception of power and of roles. In the Church there are no bosses, apart from Christ our Master; we are all servants, with different, Christ-assigned, modes of serving. Some, the clergy, with a special ministerial mission of serving (first of all) their fellow-Christians; and others, the laity, with a specific service mission to the world, so as to lead it to Christ.

The same false ecclesiological evaluation lies behind suggestions that the laity in the past have been too "subservient" to the hierarchy, and are now entitled to be liberated from this tutelage. The laity should indeed obey the hierarchy in those clear but limited areas where the hierarchy speaks with the voice of Christ. This shows faith in Christ and love for Christ. It does not show subservience. The laity do not have to be subservient to the hierarchy. They do have to serve the world, as the hierarchy has to serve them.

Again it is suggested that the laity, in contrast to pre-conciliar days, are no longer prepared to be the lunga manus, the long arm of the hierarchy, which the hierarchy uses to reach out in order to manipulate the world.

The laity are not, and were never meant to be, the "long arm" of the hierarchy. They are not a part or an extension of an official Catholic system. They, or rather each one, in his or her own right and on the basis of his or her piety and competence and doctrine, is meant to be the presence of Christ in secular affairs.

The laity do not depend on the hierarchy for their secular life, nor do they have to render any sort of account to the hierarchy for the civic or professional activities they undertake individually or in association with others. We have to remember that while Christ has a plan for the world, he has allowed for different possible modes of applying this plan. Christian lay people, working within clear though broad moral principles - but seeing things from different angles - are bound to come up with different practical solutions all of which can be regarded as legitimate Christian contributions to the proper development of human affairs (cf. GS 43). This is an expression of Christian pluralism. The hierarchy can give general moral guidelines but has no right to narrow the practical options where Christ has left them open.

"Lay leaders"

Vatican II, then, calls us to an immense broadening and deepening of vision if we are to grasp the true role of the laity. We need to get our minds off the "lay ministries" track. Lay ministries represent a valid and useful contribution, by some lay people, to the work of the clergy and the service of the Christian community. Let us not push their value or potential beyond that. Lay ministries must always, of their nature, remain non-typical for the immense majority of lay people. The documents of Vatican II in faa nowhere speak of lay ministries. These ministries - which could more properly be termed "non-ordained ecclesiastical ministries" - were introduced by Pope Paul VI in 1972[6] and, as we have pointed out, they in no way correspond to the Vatican II vision of the distinctive role and mission of the laity. They should be seen for what they were intended to be: a minor post-conciliar disposition with a certain functional or organizational utility for the internal life of the Church. It is illusory to see in them a wedge in a door through which, if forced open a little wider, the laity as a body can eventually pass and so occupy their rightful and allotted place.

This is too narrow a door for the vast majority of lay people, and the quarters on the other side are far too confined for them. The place of the laity is not the other side of that door. It lies in a different direction. Their role is not primarily participation in church organization, nor in semi-ministerial aspects of liturgical worship. It is proper participation in the life of the Church in the world, especially in that overflow of the Church's vitality which we term evangelization.

Leadership of the world - "fashioning it anew according to God's design and leading it to fulfillment" (GS 2) - is the mission and challenge that Christ, through his Church, entrusts above all to his lay followers. Lay leadership is misconceived if it is not understood in this sense. It is commonplace, in some circles, to speak of "our lay leaders" as a way of describing those who in fact are doing a (very useful) job of helping the clergy in the organization and administration of church life. We even hear expressions of satisfaction at the "growth of lay leadership", when what is meant is simply that some few lay persons (that disproportionate and wholly unrepresentative 3% or 5%!!) occupy directive positions in Catholic secretariats, are present on steering committees connected with church affairs, or lecture at ecclesiastical faculties. In all of this there is much that is useful; but there is also - in the use of the phrase "lay leaders" - much that represents the old clerical thinking rather than the new conciliar thinking.

The Council nowhere says that the laity are called to vie with the clergy for "leadership" in ecclesiastical affairs. Lay people with a genuine lay spirit have no time or interest for such intra-church competitions, and in fact find the notion comic or repellent.

The true conciliar message - addressed and open to all lay Christians and not just a clerically-inclined few - is: get out into the world; face up to the challenge of your secular calling; do your job with the fullest human competence; sanctify it; know your faith; spread it; and then you will be a true lay leader to lead the world round you to human fulfillment and to Christ.

The proper leadership potential that has to be developed, especially in young Catholics, is not for ecclesiastical tasks. Our young people are capable of more, and will be attracted by more. Their potential is to lead the world. It is a far greater challenge, and needs to be put to them.

The current rather general use of the term "lay leader" or "lay leadership" only spreads clericalism and a faulty approach to evangelization. It would be better if it were dropped. Some term such as "lay auxiliaries" could be used instead. This would avoid confusion.

"Representative" Catholics

Another phrase of doubtful validity that has come into vogue in recent years is "representative Catholics". It is a description that is commonly applied to those lay people who are involved in parish councils, who work on diocesan or national committees or secretariats, etc.

One in no way questions the value of their work in questioning whether it can be regarded as "representative" of lay Catholicism. If the true spirit of the Christian laity according to the mind of the Second Vatican Council is as outlined in this chapter, then it is clear that the lay people just mentioned represent that spirit far less than other lay Catholics whose love for Christ and zeal to make him known is expressed not within ecclesiastical structures but rather "through the structure of their secular lives" (LG 35); and whose apostolate, based on professional prestige, is expressed in normal molds of human friendship and social contact; and so, in full dedication to their secular calling, they "sanctify the world from within" (LG 10; 31).

Representative democracy is a grand phrase. Democratic representation is of course easy to speak of and quite hard to achieve in practice. Simple reflection on the sheer number, variety of jobs, personal circumstances, interests and opinions of the Christian laity, would seem to exclude the possibility of their being truly represented by any number of individuals, however chosen.

In practice the statements of principle and lines of action adopted by different Catholic lay groups - youth groups, associations of married couples, etc. - tend to represent just the thinking or decisions of a committee or a small nucleus of people. When their way of thinking or acting is in full harmony with true Christian principles, then these people may perhaps be said to "represent" Catholic ideals (though it would be truer to say that they re-echo them); but that does not make them representatives of other Catholics.

In other cases the approach to Christian living which they articulate may simply be one among the many legitimate approaches open to Christians; or, in extreme cases, it may be at total variance with Catholic teaching. In any case, whatever the views they represent, such people do not represent other persons besides themselves.

Again, we read at times of "representative gatherings" of lay Catholics meeting on a regional or perhaps a national scale. It regularly turns out that the majority attendance at these meetings is made up of people working full-time in Catholic organisms or at least deeply immersed in ecclesiastical affairs. One wonders on what grounds they can be termed "representative" of the ordinary run of lay Catholics. There might be something to be said for calling such lay people "official" Catholics, but they certainly cannot be called "representative

Some people bandy these concepts of "lay leaders" and "representative lay Catholics" as if they constituted advanced conciliar thinking and pointed the way to significant post-conciliar breakthroughs. For me all of this marks a break-through to a dead end. It is not advanced thinking; it is a continuation, in new forms, of pre-conciliar clericalism. It easily degenerates into the sterility of the power-struggle approach. It denotes a fundamental lack of understanding both of priestly "diakonia" and of the real role of the laity in the Church and in the world. It is a brake applied to evangelization.

* * *

A word of clarification is due before ending these considerations. The incidental reflections and comments of these last two chapters are mine. The substance of the ideas - on ministry and service, on the role of the priest and, especially, on the role of the laity - I owe totally to the work and thinking of Monsignor Josemaria Escriva, Founder of Opus Dei.

Msgr. Escriva was a main forerunner of Vatican II. For more than thirty years before the Council he had been preaching (and showing people how to live) the universal call to holiness, the priesthood seen as sacred service, the lay person's call to sanctify himself, his daily work, and the world around him, with a truly lay spirituality, the fundamental equality of all Christians and at the same time the functional diversity of their respective roles...

In these points, as in so many others - ecumenism, the relationship of the Church to the world and of the Gospel to culture, the dynamism of theology, the nature of evangelization - Msgr Escriva was and remains a man ahead of the times. His work and writings are an inexhaustible source of ideas and practical inspiration for all who believe that Our Lord Jesus Christ - the Son of God and "the carpenter's son" (Mt 13:54) - came to call all men to a holy life on earth and to heaven.

NOTES

[1] Attempts at "clericalization of the laity" and "secularization of the clergy" are parallel dangers that Pope John Paul II has drawn attention to (cf Insegnamenti di Giovanni Paolo Ii; VII, 1(1984), p. 1784.

[2] Emphasis added in this and the following quotations from the Council documents.

[3] Cf. Pope John Paul II, Encyclical, Laborem Exercens, 25.

[4] Cf. Pope Paul VI, Apostolic Exhortation, Evangelii Nuntiandi 70.

[5] Cf. Pope John Paul II, Encyclical, Redemptor Hominis, 21.

[6] cf. Apostolic Letter Ministeria Quaedam of 15 August 1972.