The freedom and responsibility of the laity (Homiletic and Pastoral Review, July 1993, 19-27)

[The members of the laity are projected towards the world, with a proper mission in no way subservient to the clergy.]

--------------------------------

Someone in the last century described the laity as the "shooting-hunting-fishing" members of the Church. One isn't sure if he was just a humorist or also a bit of a snob, because he clearly had the "gentry" alone - upper-class lay Catholics - in mind. In any case, humor or snobbery apart, his description is quite dickensian and dated. Nor are we likely to be more satisfied by the twentieth-century, no doubt pre-conciliar, characterization of the laity as the "praying-paying-obeying" members of the Church.

No; the role of the laity, particularly as presented by the Second Vatican Council, is something altogether different, with its own particular dignity and its own thrust and dynamism. And this is our theme: to consider what, according to the mind of the Council and to God's design, is the laity's proper role - in the Church and in the world.

Now, if one defines the role of the laity in clerical terms, one is bound to get it wrong. The laity are not the clergy in a minor key; they are not mini-priests or super-sacristans. They are not the same as the clergy or meant to be the same. They have a distinct role, neither more nor less important, but different. Laity and clergy have something fundamental in common, deriving from their one faith and their one baptism by which each becomes a son or daughter of God.[1] But the call to carry on the redemptive work of Jesus Christ, who came for the salvation of the whole world, extends to the lay person just as much as to the cleric. Each however must imitate and incarnate Christ in a distinctive way.

It is common to describe the clergy as ministers of the Church. Minister in Latin means servant. The clerical ministry is a special mission of service, [2] first and foremost towards other members of the Church. It is a sacred mission sacramentally instituted by Christ. The clergy have a peculiar charism — which lay people do not possess in the same way — to offer sacrifice and to serve and guide the community, being mediators to them of divine truth in the doctrine of the Church and of divine life in its sacraments and discipline.

The clergy are specially commissioned to minister within the Church. They can also preach to the world. But there they are "outsiders" and appear as such. The laity are specially commissioned to save and sanctify the world. They are of the world: there they are insiders, and should appear as such.

This is our theme. But before developing it, let us take a closer look at inadequate or wrong ways of conceiving the role of the laity which, as it so happens, almost always spring from a clerical mentality that in turn denotes a wrong way of conceiving the role of the clergy itself.

The clerical mentality regards the clergy as higher, with a superior status in the life of the Church; and the laity as lower, in a subordinate position. A caricature of this was the pre-conciliar cartoon: the pastor's office in the parish rectory with a big sign hanging outside saying, "I am the boss." For many people the putting into effect of the spirit of Vatican II calls for the clergy to open the office door and invite the laity in, saying, "Come, be bosses with us," while the laity for their part respond, according to their degree of progressiveness, with, "Yes, let's be bosses with you; or without you; or even against you. . . ."

Now, even if you remove the caricature from this interpretation of eclesial roles, what remains has nothing with the renewal proposed by Vatican II. It is simply a continuing reflection of the clerical mentality. If it is not overcome, it can easily lead to the idea that "promotion of the laity" consists fundamentally in lay readers at liturgical ceremonies, lay persons distributing the Eucharist, permanent deacons, more representation by lay people on Pontifical Commissions, diocesan Tribunals, parish committees, etc.; whereas none of that represents promotion of the role of the laity in the proper sense. It is simply the provision of lay helpers or auxiliaries for the work of the hierarchy or clergy. I in no way dispute the usefulness of this for the internal running of the Church; but I do maintain that it cannot provide the model for lay life - and that for two obvious reasons. The first is that such internal Church service, even in the case of those who have time for it, can occupy at only a small part of their activity as lay persons. What of the rest of their life - work, family, social relations, recreation? Has all of that - the real substance of their lay existence - no significance or only marginal significance within their proper lay vocation? The second reason is simply that very few lay people can devote even part of their time to such activities. 95% of the laity have not the time - and probably neither the calling nor the inclination - to follow such quasi-clerical ways.

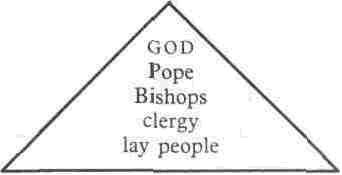

Personally, I prefer to avoid the expression "promotion of the laity," and to speak of "development of the proper role of lay people." "Promotion of the laity" can cause radical misunderstanding precisely by suggesting that the laity are in an inferior position to the clergy and that their coming of age means new and equal or almost equal rights with the clergy. In such a view authority in the Church is easily understood as domination and power, and not as service. And so one can form a picture of the Church, with its mission and structures, where ecclesial life and reform are presented in terms of a contest or struggle for "power." Many people's view of the Church corresponds in fact to what might be described as a power pyramid." Thus:

There the real power is at the top and it is shared according to one's place on the ladder up or down the pyramid. The laity are seen as on the lowest rung of the ladder, and reform or progress is under-stood as transfer of power, by means of a peaceful or forced "liberation" of lay people from clerical domination, so that they too are free to work upwards to "controlling" positions.

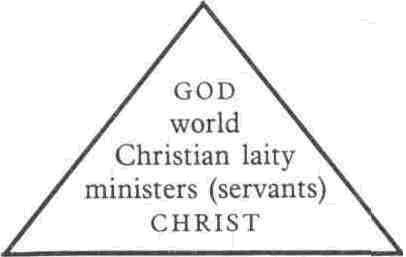

Such thinking is radically deformed. It betrays a fundamental failure to understand the nature of authority in the Church, which is a mission of service in imitation of Jesus Christ who, being Lord and Master, came not to be served but to serve. The "power-pyramid" thinking needs to be totally abandoned, if necessary by giving a revolutionary turn to one's whole outlook. In effect, if we want to represent roles in the Church graphically, we have to demolish the power-pyramid and trace instead a "service-pyramid." Thus:

Christ our Lord has chosen for himself the lowest place, that of the servant of all - so as to save all. He calls certain men - the clergy - to imitate his serving mission in a particular way (we see this reflected in the traditional title of the Pope: "servant of the servants of God"). Through his ministerial priesthood Christ specially ministers to lay Christians so that they, fulfilling their proper role, carry the sanctifying work of the Church to the world.

Through the clergy, then, Christ works to serve and vivify the laity. Through clergy and laity together he works to serve and save the world, and to raise it to God.

Here we see the scope, importance and challenge of the true role of the laity. It is through them above all that Christ must reach the world. "It is a fact," the Second Vatican Council emphasizes, "that many men cannot hear the Gospel and come to acknowledge Christ except through the lay people they associate with" (AA 13). It is in the world, not in the Church, that they have to fulfill their Christ-given apostolic mission. Some clerically-minded lay Catholics seem hungry for ecclesiastical "power." I would say to them: help the clergy where you can, always in a spirit of service; but leave the running of Church affairs to them, and you yourselves get out into the world and face up to the beautiful and difficult challenge that awaits you there.

Vatican II states emphatically that "what specifically characterizes the laity is their secular nature," and adds, "by their very vocation they seek the kingdom of God by engaging in temporal affairs and by ordering them according to the plan of God" (LG 31; cf. CL 15). So one must say that the laity are basically projected towards the world, with a proper mission in no way subservient to the clergy.

Let us try to see what in practice is involved in their role. Here we should highlight three fundamental points, preached by the Founder of Opus Dei since 1928, and taken up and solemnly taught by the Vatican Council and also especially by Pope John Paul II in his Apostolic Exhortation Christifideles Laici.

a) The lay Catholic is called to the fullness of holiness just as much as the priest or religious (LG 40-42; CL 16).

b) He is called to sanctify himself or herself in the world; "there," says Lumen Gentium, "they are called by God" (LG 31). And Christifideles Laici adds: "The world thus becomes the place and the means for the lay faithful to fulfill their Christian vocation" (CL 15).

c) He is called, as Lumen Gentium says, to sanctify the world from within (LG 31).

First, the call to sanctity. Lay Christians do not have a second rate vocation. They are equally called to friendship and intimacy with God and to a life that befits the son or daughter of such a Father. "All the faithful of Christ of whatever rank or status," says Lumen Gentium, "are called to the fullness of the Christian life and to the perfection of charity" (LG 40). The lay person uses the same means of grace as the priest or religious - prayer, the sacraments, mortification - but the life he has to sanctify is different. And here we come to the second point which concerns the place or milieu of the lay person's sanctification.

Secular activity is his or her proper field and it is this he or she must sanctify. "The characteristic of the lay state," says Vatican II, "is a life led in the midst of the world and of secular affairs" (AA 2). It is therefore in his or her worldly activity - job, business, family, social and civic life - that the lay person has specially to imitate Christ (with the Hidden Life of Nazareth particularly as model).

"God is calling you to serve him in and from the ordinary, material and secular activities of human life. He waits for us every day, in the laboratory, in the operating theater, in the army barracks, in the university chair, in the factory, in the workshop, in the fields, in the home and in all the immense panorama of work. There is something holy, something divine hidden in the most ordinary situations, and it is up to each one of you to discover it." [3]

Work well out of love for God

The requirements for sanctifying one's ordinary work could be reduced to two: working well and working out of love for God. To work well requires not only energy and effort, but also competence or human know-how (as a worker, professional man or woman, father or mother). Vatican II says that lay Christians should "labor to equip themselves with a genuine expertise in their various fields" (GS 43). This in turn takes constant study, application, research, and a readiness to learn from others.

However, as we all know from experience, it is not so difficult to work well and yet to spoil it all by working out of vanity or self-centered ambition; then of course one is not working as a Christian, for one is not working for love of Christ but for self-love. To purify one's intention in work has to be a life-long concern, and calls for an active interior life based on personal prayer and the sacraments, especially the Holy Mass. One's work, without losing its secular character, then becomes worship; a "spiritual sacrifice acceptable to God through Jesus Christ" (LG 34). And so, uniting one's everyday working life to the sacrifice of Christ on the altar, one's motives and intentions become purified little by little, and one acquires that "unity of life" on which the Founder of Opus Dei so particularly insisted. [4]

A third aspect of the lay person's mission is his or her call to sanctify the world from within (LG 10; 31): as an insider, fulfilling civic duties and exercising secular rights. Here the challenge to the lay person is great; it is not to take over the presbytery or the sacristy, but to lead the world and human affairs to Christ. People will be freely drawn to Christ if the Christians they are in contact with imbue their public or political life with a genuine spirit of service, their professional and business life with integrity and honesty, their social life with sincerity and genuine friendship, their human love and married life with generous self-giving and with the forcefulness of chastity. Life lived in such a way is immensely attractive; but it can only be lived so with the help of grace.

"For a Christian apostolate is something instinctive. It is not something added onto his daily activities and his professional work from the outside... We have to sanctify our ordinary work, we have to sanctify others through the exercise of the particular profession that is proper to each of us, in our own particular state in life." [5]

All becomes prayer

All of this implies that "unity of life" we have just mentioned. Professional work, family responsibility, personal piety and apostolate are never conflicting concerns for the Christian who has a true sense of his or her lay vocation. If it is really out of love for God that he is trying to be good and competent in his secular activities, everything he does turns into prayer and will have an apostolic impact on those around him.

To be effective apostles and witnesses to Christ in the world, Christians need:

- Competence (cf. LG 36). Christians should be hard-working and top-rate; they have to lead on merit. Lazy Christians, careless and slipshod in their work and secular duties, not only do not love God to the best of their ability, but they have no power to inspire their fellow-workers and lead them to Christ.

- Doctrine. Not only priests ought to have the answers to people's questions; so too should lay Christians. Many pagans will not even listen to a priest, but will consult or be advised by a Christian friend whose life they admire and perhaps envy. The lay person needs to study the doctrine of the Church and especially too the truths of the natural law, so as to have ready and adequate answers to people's difficulties. The Vatican II document on the Church in the Modern World says that it is the task of the laity "to cultivate a properly informed conscience and to impress the divine law on the affairs of the earthly city" (GS 43). However, the lay person's apostolate of doctrine is not achieved through "sermonizing" (the role of preacher rarely fits the lay man well), but in the normal exchange of views among colleagues and friends, where the beauty, light and warmth of Christian truth will be communicated.

- Natural virtues, in imitation of Jesus Christ, perfect God and perfect Man, whose warm and outgoing personality obviously exercised a powerful attraction on those around him. The world urgently needs to turn to God again, to learn to trust him by discovering him as a Friend. And the generous friendship they find in their Christian colleagues and neighbors should be a main means to that. This friendship may take an effort (true love and friendship always do), but it must be sincere. So lay Christians need to develop a big heart.

- Optimism: a trait that has always characterized a true Christian spirit, but which is all the more important in this moment of global loss of nerve. Deep in their hearts people are becoming pessimistic about goodness, and fearful of life. The Founder of Opus Dei, Blessed Josemaria Escriva, often spoke of himself as being "passionately in love with the world" - for it is good. "The world is good," he repeated time and again, "for the works of God are always perfect; it is we men who make the world bad, through our sins. ... we must love the world, because it is in the world that we meet God" [6]. He insisted too that "the person who knows that the world, and not just the church, is the place where he finds Christ, loves that world." [7]

In his novel, Phineas Redux, Anthony Trollope, describing the death of one of his characters, a Scotch Presbyterian, remarks that he died believing "as he had ever believed, that the spirit of evil was stronger than the spirit of good." Not a good mood in which to die; and perhaps an even worse one in which to live. That was a hundred years ago. Possibly there are many more people today who, in their hearts, share this radical pessimism. We cannot do so. We believe that God is more powerful than Satan; and also that good is stronger than evil, and more attractive in the end; and therefore that the hardest hearts, including our own at times, can be softened.

A very important passage of Vatican II's Constitution on the Church says: "The laity are given this special vocation: To make the Church present and effective in those places and circumstances where it is only through them that she can become the salt of the earth" (LG 33).

Lay mission is in the world

The scope and challenge of the laity's mission becomes evident when we say that they are meant to be the "leaders" of the world, accepted and chosen and even elected as such by their fellow citizens, by reason of their prestige, competence and honesty. We should not be afraid to use a strong expression (however open to misunderstanding) in stating that lay Christians are meant to "run" the world. They can in fact perform no greater work of service to their fellow-men than by qualifying themselves to fulfill this mission. The Council says: "The Lord desires that his kingdom be spread by the lay faithful: also the kingdom of justice, love and peace. In this kingdom creation itself will be delivered from the slavery of corruption into the freedom of glory of the sons of God... The laity enjoy a principal role in the universal fulfillment of this task" (LG 36). It is logical after all that Christian lay people should have the stuff in them to become the best guides and managers of human affairs because the Maker of the world and of man has entrusted to them the secret of what is required to create a truly human society.

What then is the lay person's relation to the clergy? Dependence on them for the sacraments, and for interpretation of the word of God. Independence as regards all else. Outside the area of dogma and legitimate discipline, each Christian is his own master. He is free to follow his own ideas, preferences and options, and is beholden to no one but his own conscience. The lay person is not a robot in the hands of the clergy, taking orders from above. He freely looks to the Church for guidance on fundamental principles of faith and morals; but after that his choices and actions are his own. Provided lay Catholics respect God's law, the clergy have no right to interfere in their political or social activity, seeking to impose one solution in areas that God has left open to men's free inquiry; nor has any bishop or priest the right to limit the personal apostolic activity of the lay person.

The peculiar mission of the laity, therefore, lies in the world. Vatican II insists that "secular duties and activity belong properly to lay people" (GS 43). The hierarchy and clergy should give authoritative guidance on the moral principles governing secular life, also on those political issues that have moral relevance. Giving such guidance is not interference in secular affairs on the part of the clergy; it is their specific right and duty. Through this intervention, the clergy show themselves as moral leaders; they do not thereby become political leaders - which is something they are not meant to be. Practical and personal involvement in politics is not a mission for the clergy; but it is for the laity (cf. CL 42). Lay Catholics need to be involved especially in public and political affairs. Blessed Josemaria Escrivá strongly resisted any suggestion that politics is a dirty business and no place for people of principle. Just the contrary, he insisted. Christians should be actively present in public life, overcoming self-centered ambition, wanting rather to serve generously and in a spirit of sacrifice. In Argentina in 1974, someone asked him how to get his friends to realize that it is God who matters, and not to be concerned about politics. Msgr. Escriva energetically replied: "but they have to be concerned. Good people need to get involved in politics... We have to get involved in the things of this earth. You and I ought to be in contact with everything that is not intrinsically evil."

The lay person's activity in the world — out of love for Christ — should be further characterized by two interconnected qualities: personal freedom and personal responsibility. Msgr. Escriva's presentation of the lay vocation insists strongly on these two qualities and on their inseparability. An awareness of freedom is at the very heart of his spirituality: "Personal freedom is essential to the Christian life." [8] "I am very fond of freedom. Without freedom we cannot be pleasing to God, nor carry out anything of worth in his presence." Just as rights imply duties, so freedom implies responsibility. And just as freedom is personal, so is responsibility. Each one must assume responsibility for his or her own free actions. The Founder of Opus Dei constantly insisted on "the principle of personal responsibility, upon which the whole of Christian morality is based." [9]

The priest who understands this freedom of the lay person will respect it and if necessary even insist that it be exercised: with the corresponding personal readiness to face up to the consequences of one's actions.

If the clergy are imbued with the service nature of their mission, they will also more readily know its limits, and realize when they are no longer obliged to give advice to the laity, and even when they are obliged not to give them advice and to insist that they must act on their own personal initiative and responsibility. The conciliar Constitution on the Church in the Modern World states emphatically: "Let the layman not imagine that his pastors are always such experts, that to every problem which arises, however complicated, they can readily give him a concrete solution, or even that such is their mission. Rather, enlightened by Christian wisdom and giving close attention to the teaching authority of the Church, let the lay man take on his own distinctive role" (GS 43).

In the work of re-evangelizing the modern Western or developed world, personal initiative in abundance is needed on the part of each Christian. The Holy Spirit breathes where he wills, and to whom he wills. Here I insist that I am not thinking of church activities, but of apostolic initiatives in the secular world: organizing a study group among neighbors or colleagues that seeks a deeper knowledge of Catholic social or moral teaching, starting a youth club or a pro-life group, launching a magazine or TV station that tries to give ordinary entertainment but with Christian standards, etc. For such activities, the lay person needs no permission or mission or authorization from any bishop or priest. He has the obligation to be active in these or similar affairs. Therefore he has the right to be involved in them and is beholden to no one except God and his conscience for such activity.

Another expression of freedom is that lay Catholics disagree with one another about concrete solutions to human problems. This is natural and good. While there is just one Catholic position on major moral issues such as abortion or contraception, there logically are several practical options open to Catholics in matters of labor relations, fiscal policies, welfare legislation, the general conduct of local, state or federal government, etc.

The breadth and flexibility of the Catholic spirit is illustrated here, also in that Catholics on different sides of the political arena should be able to disagree while retaining mutual cordiality and respect. True love for freedom means love for the freedom of others; and therefore respect for their options. [10] It is only on matters of faith and morals, I repeat, that Catholics have a common outlook. It is good spirit that in human matters they think differently; provided that this is because each one has responsibly thought out and decided on particular options; and because he is determined to respect the options of others, even if he does not follow or support them.

The Blessed Josemaria realized that for centuries the Church - ecclesiastics, that is — were being gradually pushed onto and over the sideline of worldly affairs; remaining and being looked on as outsiders. And he saw that the re-evangelization of the world must come from insiders: from those who properly belong in the world, and are not content to be just on the sideline there.

He was against the clergy going outside their distinctive role of ecclesial service, to intervene in secular affairs; and equally against the laity wanting to take on functions proper to the clergy, if this means neglecting those peculiar to them and much more challenging. Both phenomena are expressions of the clerical mentality. And that is why Msgr. Escriva often said he was anticlerical; he was against such deviations from true ecclesial roles.

His life was spent encouraging priests to fulfil their specific priestly ministry of service: and inspiring lay people to devote themselves, out of love for God, to the task of leavening the world with the spirit of Christ.

Modern pagan civilization presents a great challenge to Christians: clergy and lay people. Both share in a common task: to be instruments of God to bring the world — freely — to Christ. But each has his specific area of activity: the clergy more within the Church, the laity above all in the world. And each has his rights and obligations, his freedom and responsibility. The Second Vatican Council has urgently called on the laity in particular to wake up to their distinctive and proper role: living not as clerical deputies but as free and responsible lay persons, united individually to Christ, yet immersed in the world to which they belong and in which their secular lives are meant to become salt, light and leaven to those around them.

NOTES

[1] Cf. Lumen Gentium, 32; Christifideles Laici, 15.

[2] References to the serving mission of the clergy permeate the documents of Vatican II. Cf. for instance: Lumen Gentium 21, 24, 27, 28, 32; Christus Dominus 5, 9, 16, 28; Presbyterorum Ordinis, 3, 13,16; Gaudium et Spes 3,40,42, 76, 89, 83; Apostolicam Actuositatem 3, 8, 10, etc.

[3] Conversations with Msgr. Escriva, Ecclesia Press 1968, p. 137.

[4] Ibid., pp. 137ff.

[5] Ibid., p. 166.

[6] Ibid., p. 85.

[7] Ibid., p. 139.

[8] Ibid., p. 140.

[9] Ibid., p. 47.

[10] Cf. Christ Is Passing By, Scepter Press, 1935, pp. 169-170.