The Role of the Laity (1992 Warrane Lecture: University of New South Wales, Sydney)

Last week, giving the 1992 Warrane Lecture at the University of New South Wales, Mgr. Cormac Burke, Judge of the Roman Rota, the Church's High Court, said that lay Catholics should avoid a clerical mentality, and noted that one is bound to get the role of the laity wrong if it is defined in clerical terms. He insisted that the proper role of the laity, according to the Vatican II, is not to try to "take over" clerical functions by jockeying for "power" in the Church, but to get out into the world - both to sanctify one's own secular job there, doing it out of love for God and to the best of one's human abilities, as well as to sanctify the world itself, drawing people to Christ by example: human honesty, integrity and hard work, sincere friendship, married and family life lived faithfully.

Mgr. Burke went on: The clerical mentality regards the clergy as higher, with a superior status in the life of the Church; and the laity as lower, in a subordinate position. And he suggested this could be illustrated, caricature-wise, by the pre-conciliar cartoon which showed the parish priest's office in the parish rectory with a big sign hanging outside saying, "I am the boss". For many people the putting into effect of Vatican II calls for the clergy to open the office door and invite the laity in, saying. "Come, be bosses with us", while the laity for their part respond, according to their degree of progressiveness, with, "Yes, let's be bosses with you; or without you; or even against you"...

Even eliminating the caricature from this interpretation of ecclesial roles, what remains has nothing to do with the renewal proposed by Vatican II. It is simply a continuing reflection of the clerical mentality, which can easily lead to the idea that "promotion of the laity" consists fundamentally in lay readers at liturgical ceremonies, lay persons distributing the Eucharist, permanent deacons, more representation by lay people on Pontifical Commissions, diocesan Tribunals, parish committees, etc.; whereas none of that represents promotion of the role of the laity in the proper sense. It is simply the provision of lay helpers or auxiliaries for the work of the hierarchy or clergy. I in no way dispute the usefulness of this for the internal running of the Church; but I do maintain that it cannot provide the model for lay life - and that for two obvious reasons. The first is that such internal church service, even in the case of those who have time for it, can occupy at most only a small part of their activity as lay persons. What of the rest of their life - work, family, social relations, recreation? Has all of that - the real substance of their lay existence - only marginal significance within their proper lay vocation? The second reason is simply that very few lay people can devote even part of their time to such activities. 95% of the laity have not the time - and probably neither the calling nor the inclination - to follow such quasi-clerical ways.

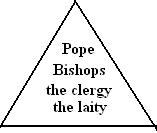

He suggested that the expression "promotion of the laity" can cause radical misunderstanding by suggesting that the laity are in an inferior position to the clergy and that their coming of age means new and equal or almost equal rights with the clergy. In such a view authority in the Church is easily seen as domination and power, and not as service. And so one can form a picture of the Church, with its mission and structures, where ecclesial life and reform are presented in terms of a contest or struggle for "power". Many people's view of the Church correspond in fact to what might be described as a "power pyramid". Thus:

There the real power is at the top and it is shared according to one's place on the ladder up or down the pyramid. The laity are seen as on the lowest rung of the ladder, and reform or progress is understood as transfer of power, by means of a peaceful or forced "liberation" of lay people from clerical domination, so that they too are free to work upwards to "commanding" positions.

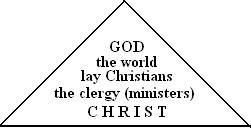

Such thinking is radically deformed. It betrays a fundamental failure to understand the nature of authority in the Church, which is a mission of service in imitation of Jesus Christ who, being Lord and Master, came not to be served but to serve... The "power-pyramid" thinking needs to be abandoned, if necessary by giving a revolutionary turn to one's whole outlook. In effect, if we want to represent roles in the Church graphically, we have to demolish the power-pyramid and trace instead a "service-pyramid". Thus:

Christ our Lord has chosen for himself the lowest place, that of the servant of all. He calls certain men - the clergy - to imitate his serving mission in a particular way (we see this reflected in the traditional title of the Pope: "servant of the servants of God"). Through his ministerial priesthood Christ specially ministers to lay Christians so that they, fulfilling their proper role, carry the sanctifying work of the Church to the world.

This suggests the scope, importance and challenge of the true role of the laity. It is through them above all that Christ must reach the world. "It is a fact", the Second Vatican Council emphasizes, "that many men cannot hear the Gospel and come to acknowledge Christ except through the lay people they associate with" (AA 13). It is in the world, not in the Church, that they have to fulfil their Christ-given apostolic mission. Some lay Catholics seem hungry for ecclesiastical "power". I would say to them - Mgr. Burke remarked - help the clergy where you can, always in a spirit of service; but leave the running of Church affairs to them, and get out into the world and face up to the beautiful and difficult challenge that awaits you there.

Vatican II states emphatically that "what specifically characterizes the laity is their secular nature", and adds, "by their very vocation they seek the kingdom of God by engaging in temporal affairs and by ordering them according to the plan of God" (LG 31). So one must say that the laity are basically projected towards the world, with a proper mission in no way subservient to the clergy.

Asking what is the lay person's relation to the clergy, Mgr. Burke replied: dependence on them for the sacraments, and for interpretation of the word of God; independence as regards all else. Outside the area of dogma and legitimate discipline, each Christian is his own master. He is free to follow his own ideas, preferences and options, and is beholden to no one but his own conscience. The lay person freely looks to the Church for guidance on fundamental principles of faith and morals; but after that his choices and actions are his own. Provided lay Catholics respect God's law, the clergy has no right to interfere in their political or social activity, seeking to impose one solution in areas that God has left open to men's free inquiry; nor has any cleric the right to limit the personal apostolic activity of the lay person.

The peculiar mission of the laity, therefore, lies in the world. Vatican II insists that "secular duties belong properly to lay people" (GS 43). The hierarchy and clergy should give authoritative guidance on the moral principles governing secular life, also on political issues which have moral relevance. Giving such moral guidance is not interference in secular affairs on the part of the clergy; it is their specific right and duty. Through this intervention, the clergy show themselves as moral leaders; they do not thereby become political leaders - which is something they are not meant to be. Practical and personal involvement in politics is not a mission for the clergy; but it is for the laity. Lay Catholics need to be involved especially in public and political affairs.

The lay person's activity in the world should also be characterized by personal freedom and personal responsibility. Just as rights imply duties, so freedom implies responsibility. And just as freedom is personal, so is responsibility. Each one must assume responsibility for his or her own free actions. The recently beatified Founder of Opus Dei, Josemaria Escriva, constantly insisted on "the principle of personal responsibility, upon which the whole of christian morality is based".

The priest who understands this freedom of the lay person will respect it and if necessary even insist that it be exercised: with the corresponding personal readiness to face up to the consequences of one's actions.

If the clergy are imbued with the service nature of their mission, they will also more readily know its limits, and realize when they are no longer obliged to give advice to the laity, and even when they are obliged not to give them advice and to insist that they must act on their own personal initiative and responsibility. The conciliar Constitution on the Church in the Modern World states emphatically: "Let the layman not imagine that his pastors are always such experts, that to every problem which arises, however complicated, they can readily give him a concrete solution, or even that such is their mission. Rather, enlightened by christian wisdom and giving close attention to the teaching authority of the Church, let the lay man take on his own distinctive role" (GS 43).

The Blessed Josemaria Escriva realized that for centuries the Church - ecclesiastics, that is - were being gradually pushed onto and over the sideline of worldly affairs; remaining and being looked on as outsiders. And he saw that the reevangelization of the world must come from insiders: from those who properly belong in the world, and are not content to be just on the sideline there.

He was against the clergy going outside their distinctive role of ecclesial service, to interfere in secular affairs; and equally against the laity wanting to take on functions proper to the clergy, if this means neglecting those much more challenging tasks peculiar to them. Both phenomena are in fact expressions of the clerical mentality. And that is why Mgr. Escriva often said he was anticlerical; he was against such deviations from true ecclesial roles. His life was spent encouraging priests to fulfil their specific priestly ministry of service: and inspiring lay people to devote themselves, out of love for God, to the task of leavening the world from within with the spirit of Christ.